Where Love Abides -- 1 John 4:7-21 (Sixth Sunday of Easter)

- Scott Clark

- May 9, 2021

- 11 min read

One of my favorite book stores is City Lights Bookstore, over in North Beach. Maybe you know it... I hope you know it. It was founded in 1953 by San Francisco poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti. I didn’t know this: It was the first all-paperback bookstore in the country. City Lights and its publishing arm are better known for being home to the Beat Generation of poets in the 1950s and 60s – Beatniks – and for moving on the leading edge of political causes and progressive thought. It was famously caught up in the obscenity trial of Allen Ginsberg’s book of poetry Howl.

It’s a funky little bookstore, right there on Columbus Avenue – now, a regular stop for both book lovers and tourists. The main floor has the fiction and literature; poetry is up a narrow staircase, in a pleasant, sunlit attic. But the basement is what fascinates me – it’s a delicious jumble of bookcases and thought and ideas. There are the usual bookstore sections: Cooking, Philosophy, Gardening. There’s History – a number of history sections, including one called The People’s History – history told not from above, but from on the ground.

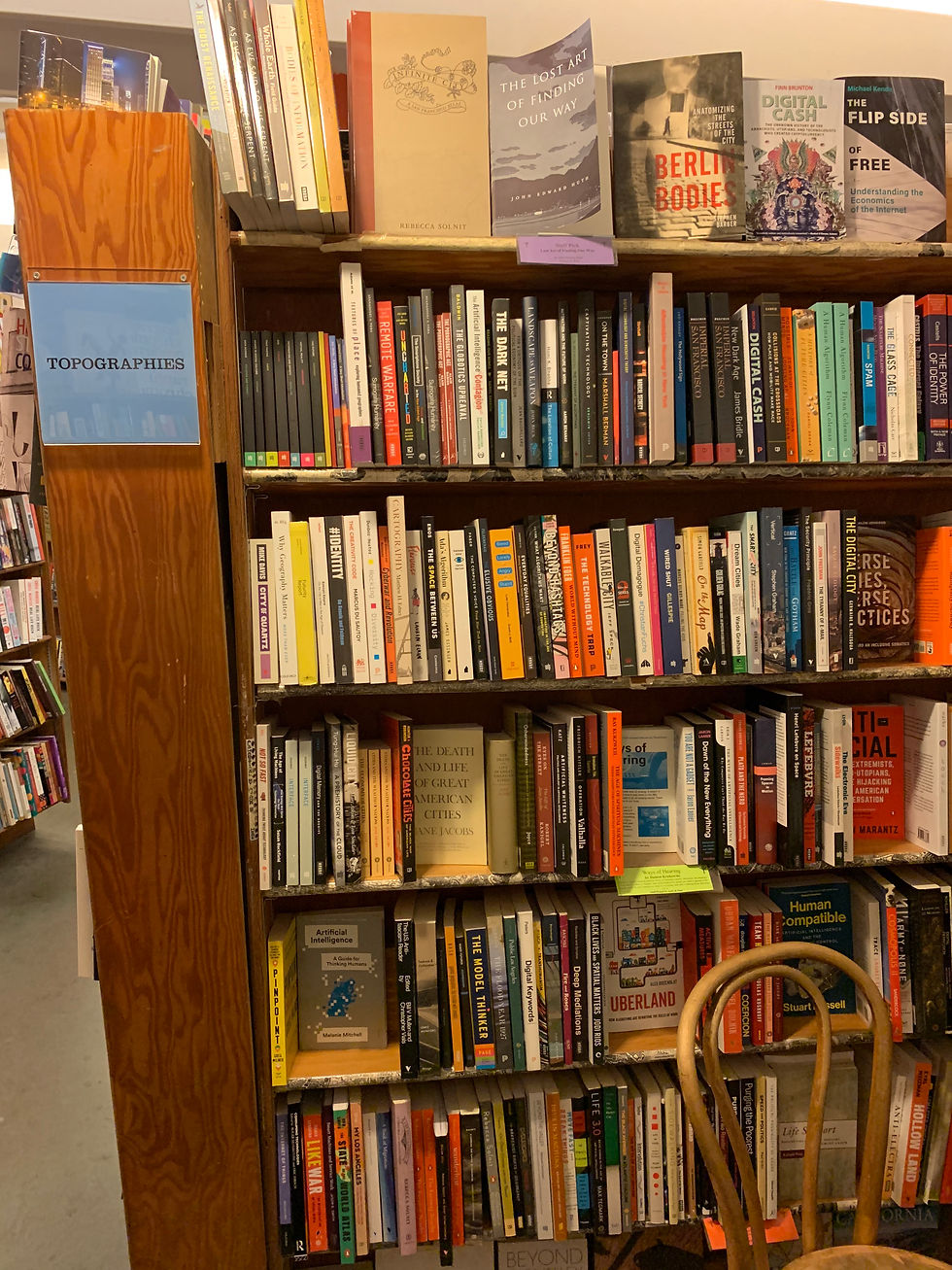

One afternoon, as I was crawling around through the basement stacks, I stumbled on a section called: “Topographies.” Topographies. Like the map you have out on a trail. It’s one big bookcase – about 7 shelves. I scanned the book titles. I know what topography is – it’s the art of describing the natural features of a place, their relative position to each other, and their structural relationships – but I couldn’t quite figure out how all the books fit together. There were books about maps and map-making and city planning. But there were also books about forming community in online spaces – and about privacy in a post-modern world and AI – artificial intelligence. And there were essays. The shelves held an odd mix of thought – assembled under the category: Topographies.

I brought some of the books that I’ve bought off of those shelves:

· There’s this one: The Lost Art of Finding Our Way. John Edward Huth – a Professor of Science – details the ways that humans, over the millennia, have found their way – by the stars, the sun, and the moon; reading the waves and the tides; with maps and compasses. He says: “Each of us is a navigator; we are constantly finding our way through our environment,” through science and subtlety learned across generations.[1]

· The Topographies section is where I found Rebecca Solnit – a Bay Area writer of essays whom I quote often. This is her book: A Field Guide to Getting Lost.[2] She writes of finding meaning in life, with great sentences like these: “Once I loved a man who was a lot like the desert, and before that I loved the desert. It wasn’t the things, but the spaces between them, that abundance of absence, that is the desert’s invitation.”

· And then, when I was working on this sermon, I found this on my bookshelves still unopened: Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas.[3] It couples descriptive essays and maps of San Francisco, like these:

-- “The Names Before the Names” – mapping Indigenous place names in the Bay Area.

-- “Monarchs and Queens” – a map of San Francisco as a safe place for butterfly sanctuaries and queer public spaces.

So, on my first encounter with this Topographies section I was wonderfully perplexed. I took the treasures I’d found upstairs to check out, and I asked the guy who was ringing me up: “What is up with this Topographies section? What’s that all about?” He chuckled, and said, “Oh, I don’t know. As best I can figure it out, it’s about how we locate ourselves and move around in spaces and places, both real and virtual.” Topographies. How we locate ourselves and move around in spaces and places both real and virtual.

First John chapter 4 offers us a topography, of where love abides – how we locate ourselves in love, and love in us, and how we move around in love, and find our way. It’s not a street map. It doesn’t read: Go this way, and then turn right, and then go one mile, and merge onto the freeway. It’s a topography – a landscape and a map to find our way over undulating hills, sometimes confronting steep cliffs; it cascades like a river, making its way down valleys, on out to the broad expanse of ocean – as we abide in God, and God abides in us – a topography of where love abides, in and with and all around us.

The physical world in which John’s community lived was a troubled one.[4] They lived in the world after crucifixion and Resurrection – a world still dominated by Empire, one of the huddled Christian communities trying to figure out what life in the body of the Risen Christ was all about. Scholars think that this letter named after John – First John – along with two others Second and Third John – was written out of the same community as the Gospel of John – probably not by the same writer, but reflecting a community of thought. Both the Gospel and this letter reflect painful disruptions in community – the Gospel has the sense that their community may have been thrown out of a larger community, maybe the synagogue. And the letters (First John included), reflect an internal schism – disputes among believers as to who Christ is. So these texts flare up from time to time – as if they’re writing against someone or someones.

But in the midst of that strife and pain, the letter we call First John grounds their life of community in love. The scripture Chris read this morning is the heart of all that. It is lush and overflowing – the words just cascade over one another – Beloved, love each other, for God is love; God’s love abides in us; we abide in God, and God in us; we love because God first loved us.

In trying to describe the structure and flow of First John 4, writers have described it as everything from “intricately woven” to “no more discernible than the waves of the sea.” “The writer writes all around a succession of topics,” and then back again, giving expression to the “shape of our existence in Christ.”[5] It is a topography – how we locate ourselves and move around in love – in God – and God in us.

And the topography that John’s community describes begins at the beginning: Love – all love – originates in God’s love for us. Love is from God; whoever loves is born of God – love no more our doing than our own birth – it is God’s gracious gift – a life lived in love. Love is how we know God. Love is made manifest in Christ. And: It’s made manifest in us – that’s how love shows up in the world. God’s love is made complete in us. We become part of the topography we inhabit – we are part of where love abides.

And then watch how love abides – how it moves in us – it’s almost like a dance – we abide in God, God abides in us. If we love each other, we abide in love. I read somewhere a long time ago “God abiding” described as God settling in and being at home in us – and we in God. The Hebrew equivalent of the Greek abiding word meno – has its roots in God pitching God’s tent with us. We were talking about this in a group I was in – and I think it was Martin who said, “It’s like God’s the tent, and we lift the flap and go on in to make our home there.” God is love and those who abide in love, abide in God, and God abides in them.

And then, as all this love is swirling around, First John gets down to the grit of it all – puts flesh on the bones. This love – it’s not some fancy feeling – it’s about life lived in community – hard life. There is no fear in love. Love throws out fear, along with any sense of vengeance or punishment. That’s not love; it’s not life; it’s not God. And. If you think you love, that’s only true if you love your sister, your brother, your sibling – it’s only love if you love that person right next to you, and the one next to them, whether or not they are easy to love, whether or not you are easy to love. You can’t say you love a God you haven’t seen, if you don’t love the human being right in front of you.

Love – real love – agape love – love lived out in the rough and tumble of community and of life – love abides in real bodies – in real people – love shows up and comes to life and moves around – in spaces and in places – in us.

I’ve been thinking about spaces and places – and topographies – how we show up in spaces and places – a lot lately, as we launch this hybrid worship experience – fusing together the community that we have found and love online, with the community we have long known in our bones in this physical space.

Think a bit about this space – the topography of this place – how folks have located themselves, ourselves – and moved around abiding in love. I think about all the worship. The baptisms. The steady rhythm of the invitation to gather at this table, to share communion. The singing, the music. This particular space opens up into the courtyard and the grounds – stunning in springtime, and there’s Duncan Hall, and all this opens up into the hills around us – and into the broader world. Think of the folks who have peopled this place, and lived life here. The body of Christ, gathered here – the love, the justice work that has been birthed and embodied here.

Noticing the topography of this place means we also have to name that the land this building sits on was inhabited by indigenous peoples long before it was stolen by European colonizers. Coastal Miwok peoples. The buildings on this property were built with capital not available to Black communities and Black people. The harms of those broken systems and structures are part of the topography – how we locate ourselves here and in the world – how we are called to abide and move around in love that honors our siblings and challenges us to tear down systems that do harm to them and the world.

We could think about the topography of our online space – how in the urgent first days of pandemic – we leapt together into this unknown world of Zoom and technology – and surprised ourselves. Think of the joy of seeing each other face-to-face each Sunday morning – together in our homes – transcending the new barriers and limitations that the world through our way – and the words we’ve shared, and the music, the choir videos, fusing music and images – the connection we’ve maintained to our work in the world, in the name of Jesus – how love abides here – how we have moved around, abiding in love, abiding in God, and God in us.

And now we are weaving together these spaces into one community – as we stretch our imaginations – and build new capacities for living life, and serving the world, and loving each other, in such a time as this – shaping a new topography for our life in Christ.

Back when I was a young lawyer, my friend Helen Kathryn and I took a backpacking class, just to have something to do that had nothing to do with the law or billable hours. We were particularly ill-suited to the project, but we had great fun together. As part of the class, we had to learn how to use topographical maps – those maps with the lines that indicate the contours of the land – they get closer together when the grade is steep, and further apart when the going is flat – they mark water features, and established paths. In teaching us how to use the topographical map, with our compass, the backpacking teacher would often say, “You need to step into the map. Step into the map, and go from there.”

Though I’m still only 70% sure what he meant by that, I want to invite us to do something like that this week.

· When you have a quiet moment, I want to invite you to step into the map – step into your life or some part of your life, and take a look around.

· Take a look around at the topography of your life – the heights, the depths, the paths, the perils, the forks in the road, the companions on the way.

· Step into your life – look around – and imagine that this is where love abides – this life is where you abide in love – where we abide in God, and God abides in us. What does that topography look like?

Abiding in love, and love abiding in you – in us – how will you locate yourself and move around in that space and place you call your life? How will we do that together? What surprises might we find there?

For the past several months, the topography of my life has been compact. It has centered in the circle at the end of Tamarindo Dr, where the street circles back on itself. So that I’ve actually lived at the corner of Tamarindo and Tamarindo. As some of you know, during my father’s illness, a neighbor generously lent her house to my sister and me – so when I’ve been in Florida – my sister and I and our partners have lived just three doors down from Mom and Dad. We have traipsed up and down that stretch of street, with dinner, and borrowed laundry racks, and dogs. The terrain of our life has included hospital rooms, and hospice beds in the living room. It has been peopled by hospice nurses and neighbors bringing groceries and meals. Our refrigerators have been full of more potato salad than any family could ever eat. Our topography has been compact, and at the same time wildly connected across the miles to the love and tender care of communities like this . Our topography has been full of deep sorrow, and also full of life and of love.

In the introduction to her Atlas of San Francisco, Rebecca Solnit points out that maps have limitations – they can only convey the information we choose to put there. They are fixed in time; they can’t capture change – as she notes, if you draw a map of a garden, just as soon as bees swarm or a new plant sprouts, it is out of date. We describe what we see – but the life we describe is inexhaustible.

In First John, the topography that the community describes – the topography of where love abides – is not so much a map we draw, as it is a world that we inhabit and create in God and with God. God has set in motion all this love and all this life – birthing us into this love – making this love manifest in Jesus Christ – and, in Resurrection and by the power of the Spirit – breathing this love and this life into us. So that. So that in our lives – with God and with the whole world – we might embody and create a world, of which we can say, this, this is where love abides.

© 2021 Scott Clark

[1] John Edward Huth. The Lost Art of Finding Our Way (Boston, MA: Harvard University Press 2013). [2] Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost (New York: Penguin Books, 2005). [3] Rebecca Solnit, Infinite City: An Atlas of San Francisco (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010). [4] This general background is drawn from Raymond E. Brown, The Community of the Beloved Disciple (New York: Paulist Press, 1979); and C. Clifton Black, “ The First, Second, and Third Letters of John,” New Interpreters’ Bible Commentary, vol. xii (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1998). [5] See Black, NIB, pp. 371-72.

Comments