At the Dimming of the Day -- Genesis 28:10-19 (15th Sunday After Pentecost)

- Scott Clark

- Sep 20, 2025

- 10 min read

Photo credit: Vincentiue Solomon, used with permission via Unsplash

As I started to think of the particular ways that we experience God (or our need for God) at the dimming of the day and on into night, I went looking for Scriptures that take place at night. There are many.

· The Bible opens in those moments just before God says, “Let there be light” – as God’s spirit broods over the dark and churning waters of creation.

· As the story unfolds, throughout Genesis, the people encounter God in dreams and night visions. God promises Abraham and Sarah that their descendants will be as numerous as the stars in the sky. Jacob, and Joseph after him, encounter God while they sleep, in dreams, and find meaning and promise there that shape the path they then take.

· At Passover, the people enslaved in Egypt head out to freedom under the cover of night. God leads them through the wilderness in a cloud by day, and in a pillar of fire by night.

· And, down through the centuries, in the midst of the daily struggles of life, at night, when all is still, the Psalms tell us that the people lament and cry out – How long O God? Help! – as they lie on their beds and pray – these prayers, like a pulse through Scripture.

· Jesus is born at night – as shepherds watch their flocks, and angels sing good news in the night sky.

· The Magi follow a star at night to find this one who has been born to set the people free.

· As Jesus lives out his ordinary days, he sleeps – just like us – he needs rest; he naps in a boat, as the disciples tremble in the midst of a violent storm.

· Jesus gathers the disciples at sundown for the Last Supper; and he prays in dark Gethsemane – like all those who had prayed the Psalms before him – “God, help, let this cup pass from me” – he prays in the deep dark of that last night.

· And then after crucifixion and resurrection and Pentecost, as the followers of Jesus try to figure things out, as they are arrested and imprisoned – at night, the prison doors fly open, and they walk to freedom.

Over the breadth of Scripture, humanity encounters God, not only in the bright light of day, but when the shadows fall, and the world becomes still.

When we are perhaps most vulnerable, God is near.

In the Scripture that Jillian read, we come upon Jacob, sleeping – about as vulnerable as he can be.[1] He’s in the middle of nowhere, running from home, but not yet arrived where he’s going – an in-between place – in the desert, at night, beneath a sky full of stars. With nothing but a large stone for a pillow, Jacob falls fast asleep.

Jacob has good reason to be exhausted. He is on the run. He has cheated his brother Esau out of his blessing and birthright... twice. Esau is enraged, and out for blood. So their mother tells Jacob to run. As she puts it, “Jacob, your brother Esau is consoling himself with plans to murder you. Run, go far away, and wait until Esau’s fury subsides” – in maybe 20 years or so. And so Jacob runs, as fast and as far as he can, and when night falls, he collapses, exhausted and spent, and he sleeps.

And Jacob has this dream. Now in the Hebrew Scriptures, in their world, dreams were real. They were one of the ways and moments that humanity communicated with God – heard from God. We live in a culture steeped in psychology – in the wake of Freud and Jung.[2] But for them dreams opened up space for actual encounters with God. As one writer puts it, dreams reflected “an actual world that can be slept on, touched, and built on” – a rock for a pillow, a stairway ascending to heaven, a voice from God.[3] In the middle of the night: “Jacob, pay attention, God is speaking. God is near.”

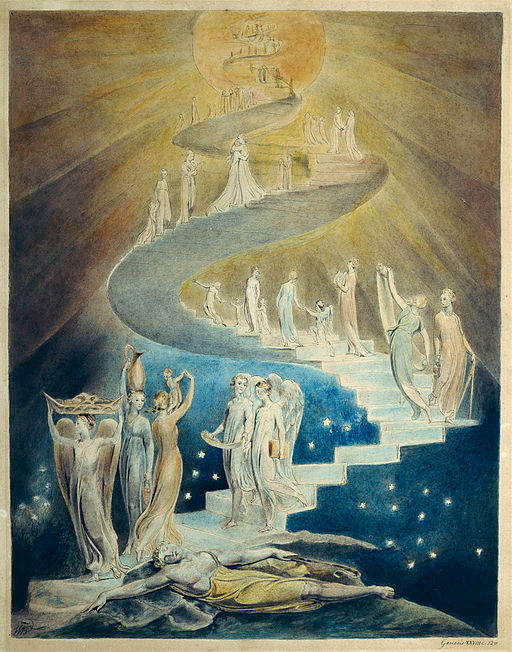

Jacob has this dream, and in the dream, he sees a stairway resting on the earth, and ascending to heaven. Now, we may be more familiar with the image of “Jacob’s ladder,” but it is really more of a staircase. If you can think of those ancient temples that we may have seen depicted in a museum somewhere – what’s called a ziggurat – with the temple at the top, and a staircase curving back and forth all the way up. It’s a staircase for going to the Temple – the place where God or, depending on the culture, the gods reside. It’s the path that humans take to meet God.[4]

Running for his life, out of the mess of his life, in the deep dark of this night, Jacob dreams of this staircase, with angels going up and coming down. And a voice says, “I am God (YHWH), the God (the Elohim) of your ancestors.” In the depths of this night, Jacob could not be any more vulnerable; his life could not be any more real; and God is near.

And then what God speaks in this dream is promise – not just one promise – no less than eight.[5] Jacob, the land you are lying on will be yours; your descendants will be like the dust, numerous and dispersed. There’s a promise of God’s blessing, a blessing not only for Jacob and his family, but for all the peoples of the earth; a promise of God’s watching and keeping; a promise of God’s presence, and that God will bring Jacob home, and that God will not leave Jacob alone.[6] Jacob wakes from this dream, bleary eyed, and says, “Surely God, Elohim, is in this place, and I did not know it.”

One scholar has noted that this text calls God by two names.[7] Yahweh Elohim. Yahweh, the God of Jacob’s ancestors – ever-present, always near – the God who shows up in bodies and with bodies. And Elohim – God of transcendence, and infinite possibility – a God not limited by the moment, but speaking a whole future into being, a future for the whole wide world.

There’s something about this story, this dream, this encounter that could only happen at night – after the fraught to and fro of daytime has grown still, all the running and rushing done – “after shadows lengthen, and evening comes, and the busy world is hushed,” when we are alone with our thoughts, our defenses down, quiet in the night – when dreams may come, and we might listen. Surely God is in this place, and I didn’t even know it.

Here are some of the ways that artists have captured this moment:

This is a very stylized image by William Blake – see that staircase wrapping back and forth.

This is Marc Chagall. So much color. Jacob’s face is red – maybe still with the flush of worry and fear. And those angels, right there with him. And yet in that deep purple, it feels like there’s more here than eye can see.

This is a traditional quilting pattern called “Jacob’s Ladder.” Alice Graham shared this with me. It goes up on a diagonal – meant to connect us here on earth with heaven. I think of parents tucking a child in at night, under this quilt, with its promise: “God is near.”

You know that spiritual, We Are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder. Enslaved people created that song and sang that song – connecting Jacob’s Ladder to the cross – the cross and Jesus connecting all those who are enslaved or oppressed to God – it is a path toward freedom.[8]

I heard something a long time ago that stuck with me: Each particular experience in life opens up particular opportunities. It’s not that they are necessarily better or worse, just different.

What are the particular human experiences that come to us at the dimming of the day and on into night?[9] One that’s at the heart of this story is the experience of vulnerability. Down through millennia, nighttime is a time when humans are particularly vulnerable – think of Jacob thousands of years ago – in a world before electricity – maybe on a night with a new moon, no light but the stars – animals prowling about, maybe other humans too. So many evening and nighttime prayers pray for protection – for God’s watching and keeping.

Nighttime is when we sleep.

But not everybody sleeps at night.

· There are those who work. Those of us who have worked a night shift know that it’s different. You’re aware that the rest of the world is sleeping – it’s just you, and the ones you’re working with, or serving. Both together and alone, in the quiet of the night.

· There are many who can’t sleep because of worry – those thoughts that keep spinning in our heads.

· There are those not sleeping because they are celebrating into the wee hours, or sharing intimacy.

· There are those who sit up at night with ones they love who are sick or dying. I remember taking my turn sleeping on the couch next to my Dad’s hospital bed, and the sound of his oxygen machine.

Down through the centuries, these human experiences particular to the night – the particular needs that humans have for God at night – they find their expression in a wealth of evening and nighttime prayers.

There’s that classic nighttime prayer – I shared it one Advent:

Watch now, dear Christ, this night

with those who work or watch or weep,

and give your angels charge over those who sleep.

Tend your sick ones, Loving Christ;

rest your weary ones;

bless your dying ones;

soothe your suffering ones;

pity your afflicted ones;

shield your joyous ones;

and all for your love’s sake. Amen.[10]

There are the psalms. Like the one that Jillian read this morning:

Answer me when I call to you O, God. Please.

When you are on your beds, search your hearts and be silent.

In peace, I will lie down and sleep,

for you alone, O God, make me dwell in safety.

The psalms – these prayers – they have evolved over time – over centuries – as people generation after generation wonder and pray and experience what it is to be human, and what it is to need and to seek God, in the quiet of the night.

Down through the centuries, and across cultures, humans have made time for prayer at night – in the regular rhythm of life. In the Jewish tradition, the day begins at sundown; the Sabbath begins at sundown – the 24-hour day begins with night, with evening prayer and rest, all in preparation for the coming day.[11]

In Christian traditions, we have traditions of evening prayer. The Benedictines call it Compline – a prayer at the “completion” of the day – followed by Vigils – prayers that keep watch through the night.[12]

I’ve tried to put an abundance of these prayers before us today. They’re in the bulletin – and on the blue sheet. Take them home. Tuck them away in your Bible. And some evening – maybe this evening, when the shadows lengthen, and the evening falls, at the dimming of the day, pull them out, and spend some time with them, in quiet.

In your experience today – as we have prayed these evening prayers (sung evening hymns) – what is different about these prayers? What have you noticed?

I’ve noticed three things that rise up out of – and really across – these prayers. First, there is the loving and gracious affirmation that God gives us rest. We talk a lot here about “the work that is ours to do.” We take that seriously: God has created us to work with God to help heal the hurt of the world. And – the God who entered fully into the human experience – has always known that we are finite, that we need sleep and rest.[13] God created Sabbath, and God created sleep and rest. There’s a line in one of these prayers: “God never sleeps, so that we can.”[14]

Next, these prayers affirm and trust that God keeps watch. Down through the generations, in the vulnerability of what it is to be human, folks have prayed for God to keep watch when we cannot. These prayers don’t magically stop all bad things – they affirm again and again the promise that God will always be near. God will not and does not leave us alone.[15]

And last thing: These prayers are lovely. They are some of the most lovely prayers I know – for those tender moments when we may need God the most.

Our “something to do” this week is the gift of these prayers. They are a gift from those who have come before us – those as thoroughly human as us – those who, with us, have known what it is to long for God at the dimming of the day. Our “something to do” in this not-so-ordinary time is the grace-abounding invitation to integrate into our work and living the rest and the peace that God desires for every living being – so that we might help others find that rest and peace in the troubles of their lives – in the troubles of our world – so that we might rise, together, with Jacob, in the promise of a new day, and say, “Oh. Surely God is in this place. And I didn’t even know it.”

© 2025 Scott Clark

[1] For general background on this text and Genesis, see Terence E. Fretheim, “The Book of Genesis,” New Interpreters’ Bible Commentary, vol. I (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1994); Herman C. Waetjen, Christianity as the Moral Order of Integration: The Gift of the Jews to the World (London: Austin Macauley Publishers, 2023), pp.82-96; Valerie Bridgeman, Commentary on Working Preacher, at https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/ordinary-16/commentary-on-genesis-2810-19a-6

[2] For a reading of Genesis stories that uses an explicitly psychological lens, see Naomi H. Rosenblatt and Joshua Horowitz,Wrestling with Angels: What Genesis Teaches Us About Our Spiritual Identity, Sexuality, and Personal Relationships (New York, NY: Dell Publishing, 1995).

[3] See Fretheim, p.542.

[4] See Fretheim, p.541; Menn, supra.

[5] See Fretheim, p.541.

[6] Id.

[7] See Waetjen, pp.35-42, 87-88.

[8] See Bridgeman, supra.

[9] For an excellent, extended treatment of prayer at night, see Tish Harrison Warren, Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2021), and Tish Harrison Warren, Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2016), pp. 140-152.

[10] I was first introduced to this prayer in the prayers of the Iona Community of Scotland, and the particular wording offered here follows theirs (slight difference in syntax from the Anglican). See, supra, Tish Harrison Warren, Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2021).

[11] See Tish Harrison Warren, Liturgy of the Ordinary, p.150.

[12] See Prayer in the Night, p.12.

[13] See Liturgy of the Ordinary, pp.144-150.

[14] This line comes from an evening prayer response of the Iona Community.

[15] See Prayer in the Night, p.32 (“God will keep close, and we will not be left alone.”)

Comments